Savannah, Georgia

History and Low Country Charm

After a seven hour run north from South Florida on I-95, the city of Savannah on Georgia’s southeast coast exudes fragrant whiffs of Southern charm. It seduces with 22 city squares, over 1800 historic homes, churches and sites, a high bluff on lively River Street, and delicious Low Country dishes like shrimp and grits, crab cakes or pan-fried flounder. The state’s oldest city it dates back to General James Edward Oglethorpe in 1733 who plotted the original settlement in a grid format (“wards”) that remains nearly faithful today with its myriad of architectural styles, from Georgian and Gothic to Greek Revival and Early Skyscraper.

With its historic center location on Reynolds Square a block from River Street, the 200-year-old Planter’s Inn offers complimentary continental breakfast, a nightly wine and cheese reception, and 60 attractive renovated rooms with turndown service and plush bathrobes. I found the staff to be gracious and hospitable while the valet service is a huge convenience for drives to outlying attractions like nearby Tybee Island (Savannah’s Beach), Fort Pulaski and Bonaventure Cemetery (made famous in John Berendt’s 1994 bestseller, Midnight in the Garden of Good and Evil).

To better understand the layout take a breezy overview of Savannah’s major squares and local personalities on Old Savannah Tours with its 14 trolley “on/off” stops starting at Savannah’s Visitor Center on the west side’s Martin Luther King, Jr. Boulevard. Even better, we took Savannah College of Art and Design-graduate Jonathan Stalcup’s Architectural Tours from nearby Washington Square on a fascinating chronological walking tour of stately mansions and monuments. On Oglethorpe Square he pointed out William Jay’s masterpiece of English Regency at Telfair’s Owens-Thomas House (1819) with its famous double-curved outside staircase, Ionic columns, cast iron Grecian balcony, courtyard “parterre” gardens, slave quarters, original basement kitchen and cistern, and unusual second floor interior wood “bridge”. The slave quarters are stark reminders of how cotton and rice built fortunes on nearby ante-bellum plantations.

The more modest and homey Davenport House Museum (1820), a block away on Columbia Square, shows New England transplant-builder Isaiah Davenport’s penchant for pragmatic “American” solutions. His Federal-style, rectangular brick exterior encloses an elliptical staircase with flanking rooms, colorful period wallpaper in the upstairs bedrooms, ornate plasterwork, and original flooring. Interestingly, the house became a tenement by the mid-1950s and prompted seven Savannah women to save it from demolition, thereby creating the Historic Savannah Foundation, a major catalyst for its thriving preservation movement.

The past and the dead partially define the city. A few blocks south the eerie but fascinating Colonial Park Cemetery (1750) contains pioneers from the Revolutionary War, graves of 1820 yellow fever victims, and tombstone graffiti from bivouacked Civil War Union soldiers. Walking northwest across Drayton to Bull Street brings you to the late 19th century Juliette Gordon Low Birth-Place, the city’s first National Historic Landmark in honor of the founder of Girl Scouts of the USA. West on Barnard Street, Telfair Square epitomizes the city’s love-hate affair with eclectic architecture: Moshe Safdie’s Telfair’s Jepson Center for the Arts (2006), a post-modern statement of huge glass façade, Portuguese limestone, massive interior staircase, and Noguchi statues on the “carriage house” terrace; Telfair Academy, William Jay’s other Regency construction with Corinthian columns, and the oldest art museum in the South. Surprisingly, anchored by the tranquil square, the two architectural rhythms seem to work.

Jonathan urged us to follow the circuit of churches that dot the main squares: Madison’s St. John’s Episcopal Church and its historic iron portico parish hall, the Green-Meldrim House, headquarters for Union Commander, General William Tecumseh Sherman; Monterey’s Gothic-Moorish Congregation Mickve Israel, the first Jewish congregation in the South; Lafayette’s twin-spire Cathedral of St. John the Baptist’s ornate altar and stained glass windows. Diagonal to the Catholic cathedral sits the 1849 Andrew Low House (Juliette’s father-in-law), an Italianate villa filled with valuable period furnishings where Juliette lived until her death in 1927. Just to the south, don’t miss Forsyth Park with its stunning Parisian-inspired grand fountain and handsome Victorian mansions that line the lush 30 acres.

With the welter of tours available we decided to dig deeper into the African American experience through Day Clean Journeys. Our guide A.J. Toure picked us up at the Planter’s Inn and drove us to nearby Franklin Square and the First African Baptist Church (1859) with its distinctive red door, stained glass windows, handmade pews with Arabic writing, and basement escape holes for the Underground Railroad. The very knowledgeable Toure not only provides vital information on the plight of “captives” (slaves) and freedmen but laces descriptions with Gullah (creole) words and phrases.

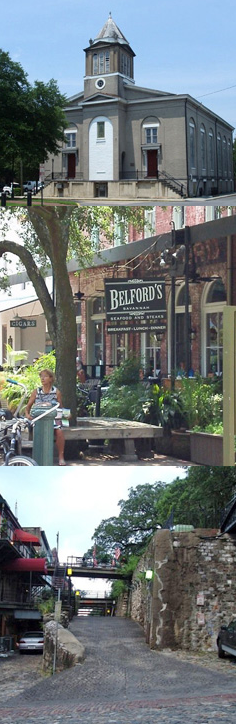

Inevitably, walking tours produce hearty appetites. Across Franklin Square and its monument to American Revolutionary War Haitian volunteers, stop at Belford’s Savannah in City Market. The 1902 red brick building with arched toplights was originally built for the Savannah’s Hebrew Congregation but now serves delicious premium jumbo lump crab cake, she crab stew, and certified Angus beef. Next door to the Planter’s Inn sits distinctively The Olde Pink House Restaurant, built in 1771 by the wealthy Habersham family and beautifully preserved with original mantels, mullions, heart pine flooring, hideaway shutters, a Thomas Jefferson-designed dumb waiter (Purple Room), and vault wine cellars. Our lunch of pecan crusted chicken with bourbon sauce, fried green tomato crab cake, and crispy lobster tail with bacon buttermilk mashed potatoes was topped off with a terrific “dry” pecan pie with dark chocolate.

Dinner below ground in the Colonial cellars of Alligator Soul off Telfair Square comes with a distinct New Orleans flair. Owners Maureen and Hilary Craig serve an excellent Jambalaya with fresh local shrimp and Carolina rice, Oysters Bienville with crawfish and andouille sausage, and mint julep lamb chops accompanied with rutabaga celeriac gratin with Fontina cheese. For dessert there’s Irish coffee bread pudding and banana beignets. On East Bay Street parallel to River Street enter an original Revolutionary-era rough brick tavern at B. Matthew’s Eatery. Besides their popular breakfast of made-from-scratch biscuits and gravy or lunchtime black-eyed pea “veggie” burger, the dinner is reasonable and sophisticated: a very fine wild mushroom and goat cheese strudel, fresh spinach fettuccini, quail and dumplings, and braised pork osso bucco. Owner Brian Huskey also runs Blowin’ Smoke BBQ on MLK Blvd. where the pulled pork and dipping sauce earn high marks.

The River is the other face of Savannah. On the bluff renovated cotton warehouses and rough cobblestones now host throngs of visitors nightly. We ended our stay with an evening dinner cruise on the triple-decker “Savannah River Queen” run by River Street Riverboat Company. Besides a surprisingly tasty buffet, we passed under the I-95 bridge and port before heading downriver past tidal islands to Fort Jackson, Georgia’s oldest standing fortification. Returning upriver the soft breeze and moonlight spelled magic as the lights of the city flickered.

Charles Greenfield is a Miami-based travel writer who has contributed to Travel + Leisure and regional magazines/newspapers. He also is Cultural Arts Contributor to Artsbeat on WLRN 91.3 FM, South Florida’s NPR affiliate, a producer for WLRN Ch. 17’s Artstreet, and has written on classical and jazz musicians for the Miami Herald.